Theory

Introduction

What is theory?

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a theory is "an idea that is suggested or presented as possibly true but that is not known or proven to be true." This is distinct from a law, "a statement of an order or relation of phenomena that so far as is known is invariable under the given conditions."

There is a good chance that right now, you're incredible overwhelmed by all of the different aspects of policy debate, from the structure of a card to the expectation to talk almost inhumanly quickly. So, it may come as a surprise when I tell you the truth: policy debate doesn't actually have many solid rules, or laws. Instead, how we debate (or how we're expected to debate) operates on theories of how we should. While kritiks may challenge certain aspects of debate on a philosophical level, theory is an argument about the rules of debate, arguing why we should or shouldn't debate a certain way to keep the debate fair and educational.

According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, a theory is "an idea that is suggested or presented as possibly true but that is not known or proven to be true." This is distinct from a law, "a statement of an order or relation of phenomena that so far as is known is invariable under the given conditions."

There is a good chance that right now, you're incredible overwhelmed by all of the different aspects of policy debate, from the structure of a card to the expectation to talk almost inhumanly quickly. So, it may come as a surprise when I tell you the truth: policy debate doesn't actually have many solid rules, or laws. Instead, how we debate (or how we're expected to debate) operates on theories of how we should. While kritiks may challenge certain aspects of debate on a philosophical level, theory is an argument about the rules of debate, arguing why we should or shouldn't debate a certain way to keep the debate fair and educational.

Fairness and education? That sounds a little bit like topicality.

Right you are, young cricket. In fact, topicality is actually a type of theory argument ("the affirmative MUST be topical"). So, it shouldn't be surprising that other theory arguments are structured very similarly to topicality arguments when it comes to standards and voters. An example of a theory argument is shown in the following section.

How does theory operate in the round?

Like topicality, theory is a procedural argument, which comes before any other argument in the round. Essentially, this means that no matter how badly you are losing every other argument in the round, if you pursue a successful theory argument, you win the round. The idea is that deciding on the rules of debate and ensuring fairness is a priority in debate rounds, because if the debate is unfair to begin with, productive discussion of the resolution cannot actually happen.

Theory arguments can either be put on specific flows (like a specific counter-plan or kritik), or it can be its own separate piece of paper.

Right you are, young cricket. In fact, topicality is actually a type of theory argument ("the affirmative MUST be topical"). So, it shouldn't be surprising that other theory arguments are structured very similarly to topicality arguments when it comes to standards and voters. An example of a theory argument is shown in the following section.

How does theory operate in the round?

Like topicality, theory is a procedural argument, which comes before any other argument in the round. Essentially, this means that no matter how badly you are losing every other argument in the round, if you pursue a successful theory argument, you win the round. The idea is that deciding on the rules of debate and ensuring fairness is a priority in debate rounds, because if the debate is unfair to begin with, productive discussion of the resolution cannot actually happen.

Theory arguments can either be put on specific flows (like a specific counter-plan or kritik), or it can be its own separate piece of paper.

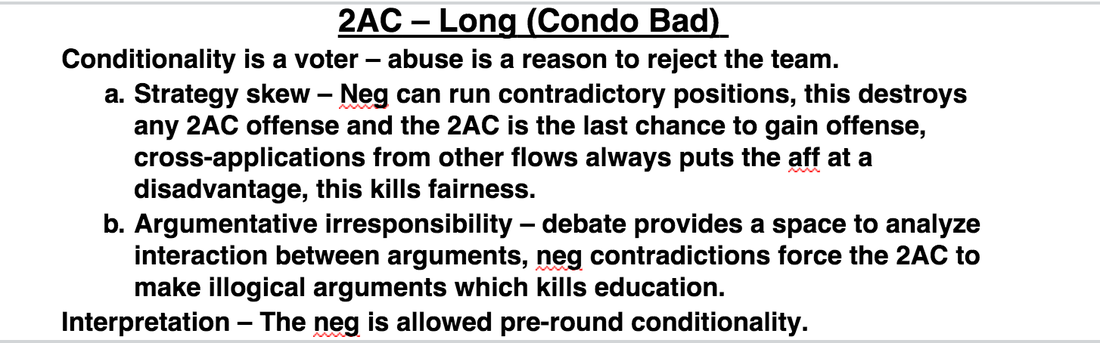

Here's an example of a common theory argument.

...Yeah, that's confusing. Let's break it down.

First, a little background: Conditionality is an advocacy status. When the negative team has multiple off-case positions (such as running multiple counterplans and contradicting kritiks all at the same time), they may choose for their positions to be conditional, which means that they can kick out of these arguments at any time during the debate and pursue their best argument in the 2NR. This is the opposite of unconditional, which means that that argument must remain constant and cannot be dropped, the negative team has to pursue the off-case argument in the 2NR.

While having conditional off-case positions may be strategic for the negative team, it often hurts the affirmative side. There are two major ways why this is the case:

1) The argument assumes that the affirmative team will likely answer one off-case position better than others in the 2AC, which means that the negative team can simply kick out of that one argument and rely on the one that wasn't answered as well. At that point, the 1AR is pretty late and time-pressed to make new and better arguments, so it's very unlikely for the affirmative to be able to recover and win the debate.

2) Conditionality also allows for the negative team to make contradicting arguments. Then, whatever the affirmative team says for one argument, the negative can cross-apply to the other flow and get concessions. (Ex. The negative could run a disadvantage that the plan devastates the economy, then run a capitalism kritik. The affirmative could argue that they actually help the economy. Then in the next speech, the negative could simply kick out of the disadvantage and gain more leverage for their capitalism kritik by saying that the affirmative is concerned with participating in the free market.)

1) The argument assumes that the affirmative team will likely answer one off-case position better than others in the 2AC, which means that the negative team can simply kick out of that one argument and rely on the one that wasn't answered as well. At that point, the 1AR is pretty late and time-pressed to make new and better arguments, so it's very unlikely for the affirmative to be able to recover and win the debate.

2) Conditionality also allows for the negative team to make contradicting arguments. Then, whatever the affirmative team says for one argument, the negative can cross-apply to the other flow and get concessions. (Ex. The negative could run a disadvantage that the plan devastates the economy, then run a capitalism kritik. The affirmative could argue that they actually help the economy. Then in the next speech, the negative could simply kick out of the disadvantage and gain more leverage for their capitalism kritik by saying that the affirmative is concerned with participating in the free market.)

Prime examples of rejection are commonly shown on "The Bachelor."

Prime examples of rejection are commonly shown on "The Bachelor."

So, keeping these concepts in mind, let's figure talk about how we format these arguments in round. There is not a specific way or order a theory block has to be written, but there are several components that make up a theory argument:

Proof of Abuse or Potential Abuse

In this case, abuse comes in the form of "strategy skew" and "argumentative irresponsibility." Notice that both of these have impacts: a decrease in fairness and a decrease in education. Theory arguments must have these standards/impacts, or else there really isn't a reason to vote on theory or reject the team.

Statement that ___ is a voter and a reason to reject the team.

In-round abuse happened and it harms education and fairness -- so what? Is that something the judge can vote on? In policy debate, you could go on and on about how the other team is bad in this and that way, but if you don't explicitly say it's a voting issue, then it isn't something that wins you the round. (Think about arguing on-case: If you make a no-solvency argument in your first speech, but you don't explain why no-solvency arguments are important, why should you win the round?)

Proof of Abuse or Potential Abuse

In this case, abuse comes in the form of "strategy skew" and "argumentative irresponsibility." Notice that both of these have impacts: a decrease in fairness and a decrease in education. Theory arguments must have these standards/impacts, or else there really isn't a reason to vote on theory or reject the team.

Statement that ___ is a voter and a reason to reject the team.

In-round abuse happened and it harms education and fairness -- so what? Is that something the judge can vote on? In policy debate, you could go on and on about how the other team is bad in this and that way, but if you don't explicitly say it's a voting issue, then it isn't something that wins you the round. (Think about arguing on-case: If you make a no-solvency argument in your first speech, but you don't explain why no-solvency arguments are important, why should you win the round?)

Interpretation

Think about topicality interpretations: the negative is proposing an alternative definition to a word that the affirmative doesn't meet. With theory, the affirmative is proposing an alternative view of debate that the negative hasn't followed. To put it simply, the interpretation is a statement of what the other team is allowed to do. In the theory argument above, the interpretation is that the negative team can have pre-round conditionality (which, from what I understand, is really just another way of saying "unconditionality," arguing that the negative has a sufficient amount of time to develop a good strategy).

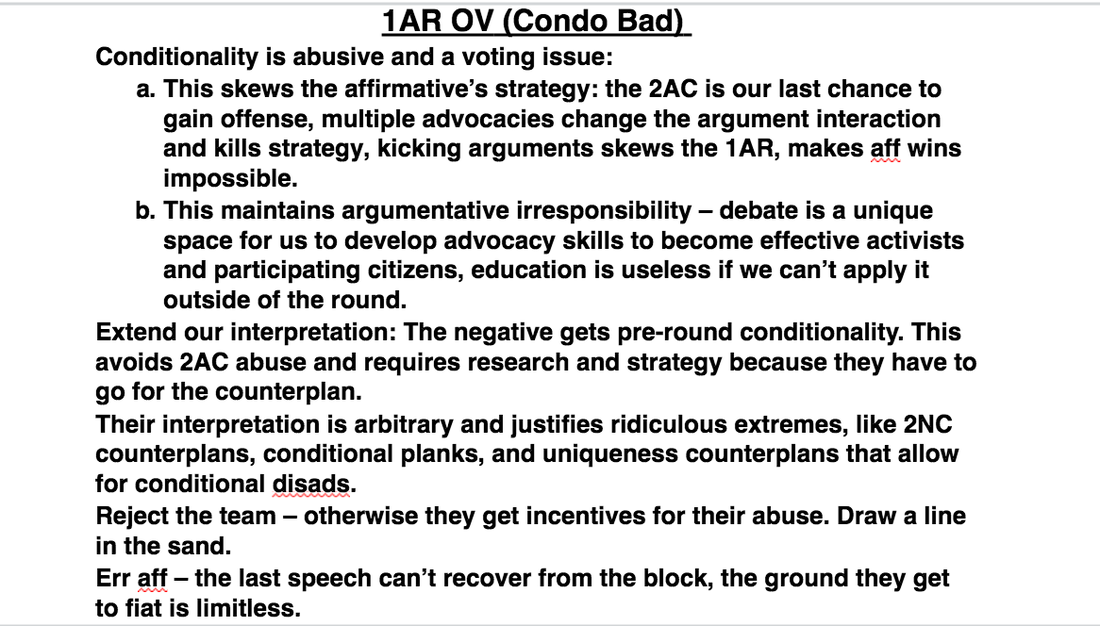

Err aff on theory.

"Err (your side) on theory" prompts the judge to vote for your side on theory just because the other side has a competitive advantage in some way. So, if I were aff, I may say, "Err aff on theory, because the negative gets the block and can control the direction of the debate by choosing their most prepared strategies to enter the debate."

Think about topicality interpretations: the negative is proposing an alternative definition to a word that the affirmative doesn't meet. With theory, the affirmative is proposing an alternative view of debate that the negative hasn't followed. To put it simply, the interpretation is a statement of what the other team is allowed to do. In the theory argument above, the interpretation is that the negative team can have pre-round conditionality (which, from what I understand, is really just another way of saying "unconditionality," arguing that the negative has a sufficient amount of time to develop a good strategy).

Err aff on theory.

"Err (your side) on theory" prompts the judge to vote for your side on theory just because the other side has a competitive advantage in some way. So, if I were aff, I may say, "Err aff on theory, because the negative gets the block and can control the direction of the debate by choosing their most prepared strategies to enter the debate."

How to Answer Theory Arguments

Keeping the above in mind, answering theory arguments are actually pretty intuitive:

Disprove abuse and/or argue that potential abuse isn't a voter.

This is pretty easy to do if you aren't abusive in round. Per se you are on the negative team defending your conditional off-case positions: You may argue that your off-case positions are super generic and should be predictable. You could argue that you aren't running any contradicting arguments, or that if you are, you won't cross-apply the affirmative's defense from one flow to another. You can easily argue that the other team can only win on theory if they prove actual abuse happened, because theory is a way to punish teams that are abusive, not teams that could've been abusive but weren't.

Make a statement that ___ is NOT a voter and is NOT a reason to reject the team.

This is a broader statement saying that whatever the other team is criticizing you for is not actually a voter and not a reason to reject the team. Defending conditionality, you would simply say: "Conditionality is NOT a voter and is NOT a reason to reject the team." The following points will be reasons why this statement is true.

Disprove abuse and/or argue that potential abuse isn't a voter.

This is pretty easy to do if you aren't abusive in round. Per se you are on the negative team defending your conditional off-case positions: You may argue that your off-case positions are super generic and should be predictable. You could argue that you aren't running any contradicting arguments, or that if you are, you won't cross-apply the affirmative's defense from one flow to another. You can easily argue that the other team can only win on theory if they prove actual abuse happened, because theory is a way to punish teams that are abusive, not teams that could've been abusive but weren't.

Make a statement that ___ is NOT a voter and is NOT a reason to reject the team.

This is a broader statement saying that whatever the other team is criticizing you for is not actually a voter and not a reason to reject the team. Defending conditionality, you would simply say: "Conditionality is NOT a voter and is NOT a reason to reject the team." The following points will be reasons why this statement is true.

Present reasons why ___ is good and/or inevitable.

Simply, these can be thought of as counter-standards, because you can think of these as points as to why you either 1) don't detract from the fairness and education in the round or 2) you actually access fairness and education in the round. In the case of defending conditionality, you may say that conditionality is inevitable so long as there is more than one off-case position. You may say it's reciprocal, because the affirmative team can kick out of advantages. You may say you access education better, because conditionality better resembles "real-world policy making," since policymakers have to test potential laws from different angles and perspectives before passage.

Counter-Interpretation

This is a statement of what your team is allowed to do. Defending conditionality, you may say: "The negative team is allowed one conditional kritik and one conditional counterplan." That seems pretty reasonable.

Err neg on theory.

This is the literal opposite of "Err aff on theory." You could say, "Err neg on theory, because the affirmative has the first and last speech, can choose the topic of the debate, and use infinite prep."

Simply, these can be thought of as counter-standards, because you can think of these as points as to why you either 1) don't detract from the fairness and education in the round or 2) you actually access fairness and education in the round. In the case of defending conditionality, you may say that conditionality is inevitable so long as there is more than one off-case position. You may say it's reciprocal, because the affirmative team can kick out of advantages. You may say you access education better, because conditionality better resembles "real-world policy making," since policymakers have to test potential laws from different angles and perspectives before passage.

Counter-Interpretation

This is a statement of what your team is allowed to do. Defending conditionality, you may say: "The negative team is allowed one conditional kritik and one conditional counterplan." That seems pretty reasonable.

Err neg on theory.

This is the literal opposite of "Err aff on theory." You could say, "Err neg on theory, because the affirmative has the first and last speech, can choose the topic of the debate, and use infinite prep."